What do physicians and stent companies have to say for themselves, given that they promote expensive, risky procedures with no benefit?

“Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)”—angioplasty and stent placement—“continues to be frequently performed for patients with stable [non-emergency] coronary artery disease, despite clear evidence that it provides minimal benefit…” The procedure does not prevent heart attacks or death for patients with stable angina pectoris, for example, yet nearly nine out of ten patients mistakenly believed that it would reduce their chances of having a heart attack. “At the same time, the cardiologists who referred them for PCI and those who performed the procedure generally did not believe that PCI reduces the risk for MI [myocardial infarction or heart attack] in stable angina.” Then why on earth were they doing it?

“Focus groups of cardiologists have documented a chasm between knowledge and behavior; while aware of the results of clinical trials”—that is, evidence to the contrary—“they recommend and perform PCI because they believe that it helps in some ill-defined way.” “Physicians tended to justify a non-evidence-based approach (‘I know the data shows there is no benefit, but’) by focusing on the ease of PCI and belief that an open artery was better”—even if it doesn’t actually affect outcomes—“while minimizing the risks of PCI.” The procedure only kills 1 in 150, so some are blaming the patients for not listening, but maybe the physicians are the ones who are ignoring the evidence.

Or “physicians may have too poor a grasp of relevant statistics to adequately inform their patients.” Regardless, what we have is “a failure to communicate.” So, tools have been developed. For example, a sample informed consent document lays out the potential benefits and risks, even laying out how many procedures doctors have performed and any out-of-pocket costs. As you can see below and at 1:58 in my video Angioplasty Heart Stent Risks vs. Benefits, there are a lot of blanks to be filled in. What are some concrete numbers?

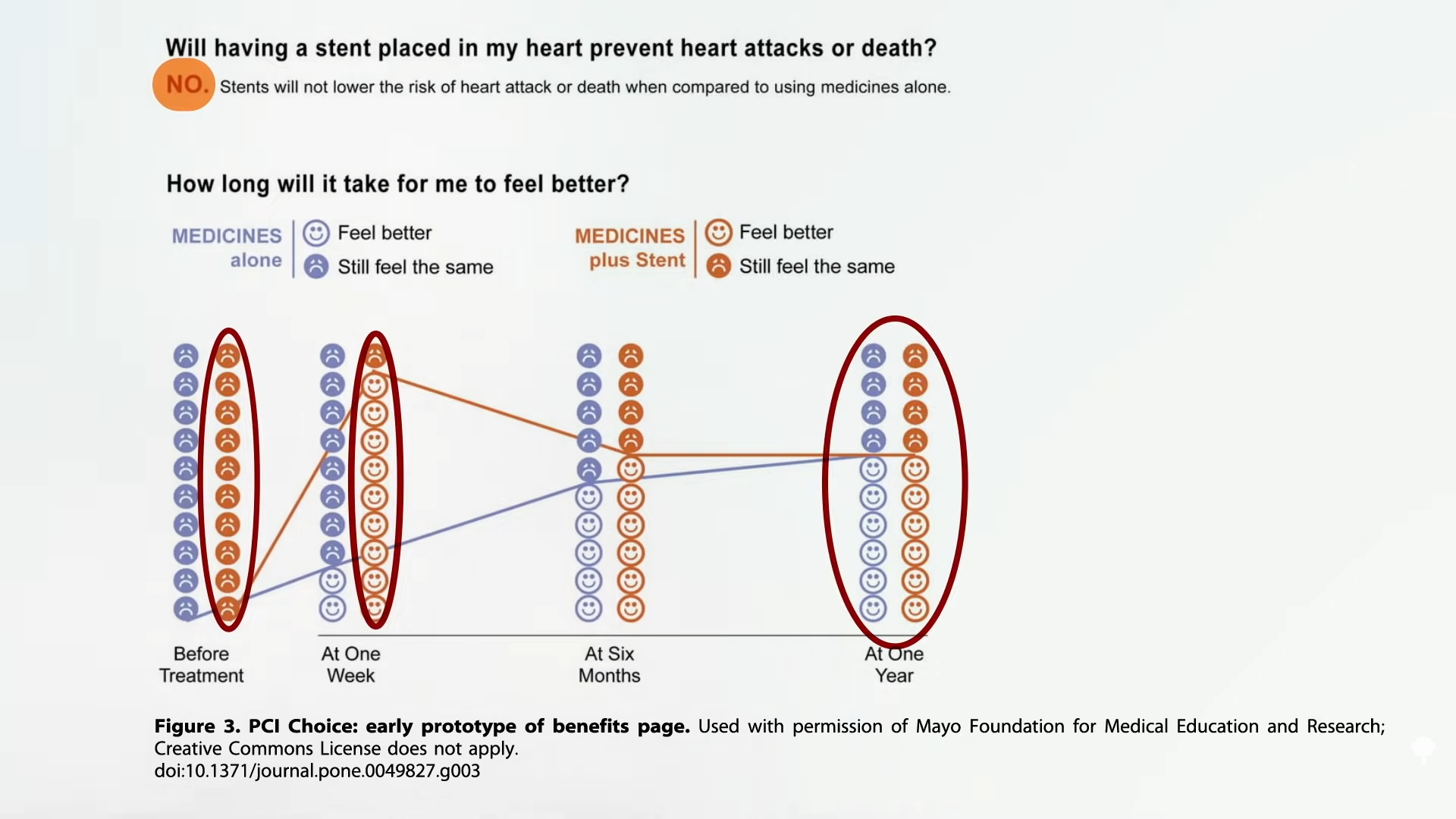

As you can see below and at 2:20 in my video, the Mayo Clinic came up with some prototype decision-making tools. In terms of benefits, “Will having a stent placed in my heart prevent heart attacks or death? No. Stents will not lower the risk of heart attack or death,” but a week later those getting stents report they feel better—though, a year later, even the symptomatic-relief benefit appears to disappear. Nevertheless, there appeared to be a benefit of temporary relief of chest pain. What about the risks?

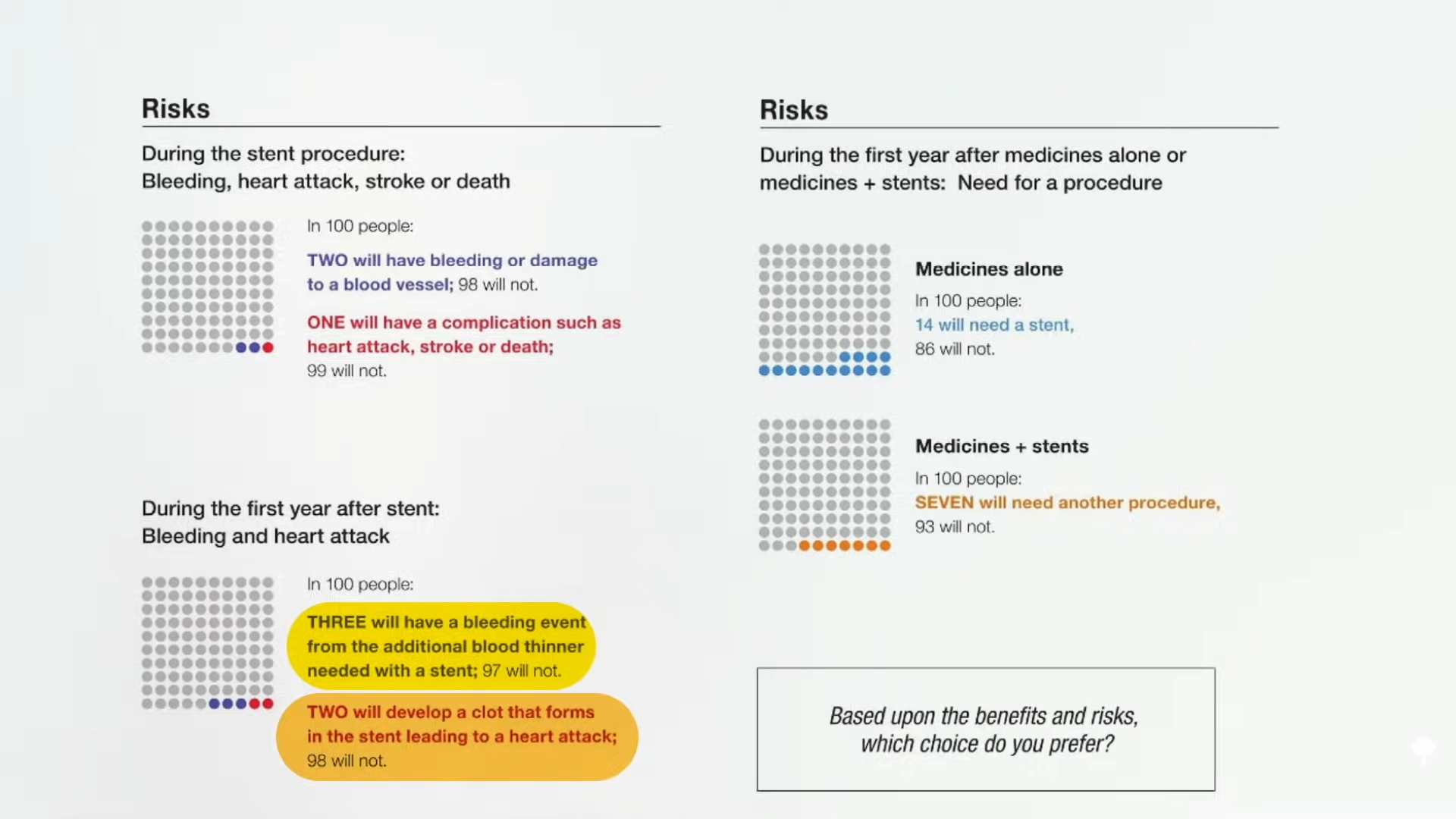

As shown below and at 2:53 in my video, during the stent procedure, out of a hundred people, two will have bleeding or damage to a blood vessel and one will have a more serious complication, such as heart attack, stroke, or death. Then, during the first year after the stent placement, three will have a bleeding event because of the blood thinners that must be taken because of the foreign material in the heart, but that doesn’t always work, so two people will have their stent clog off, leading to a heart attack.

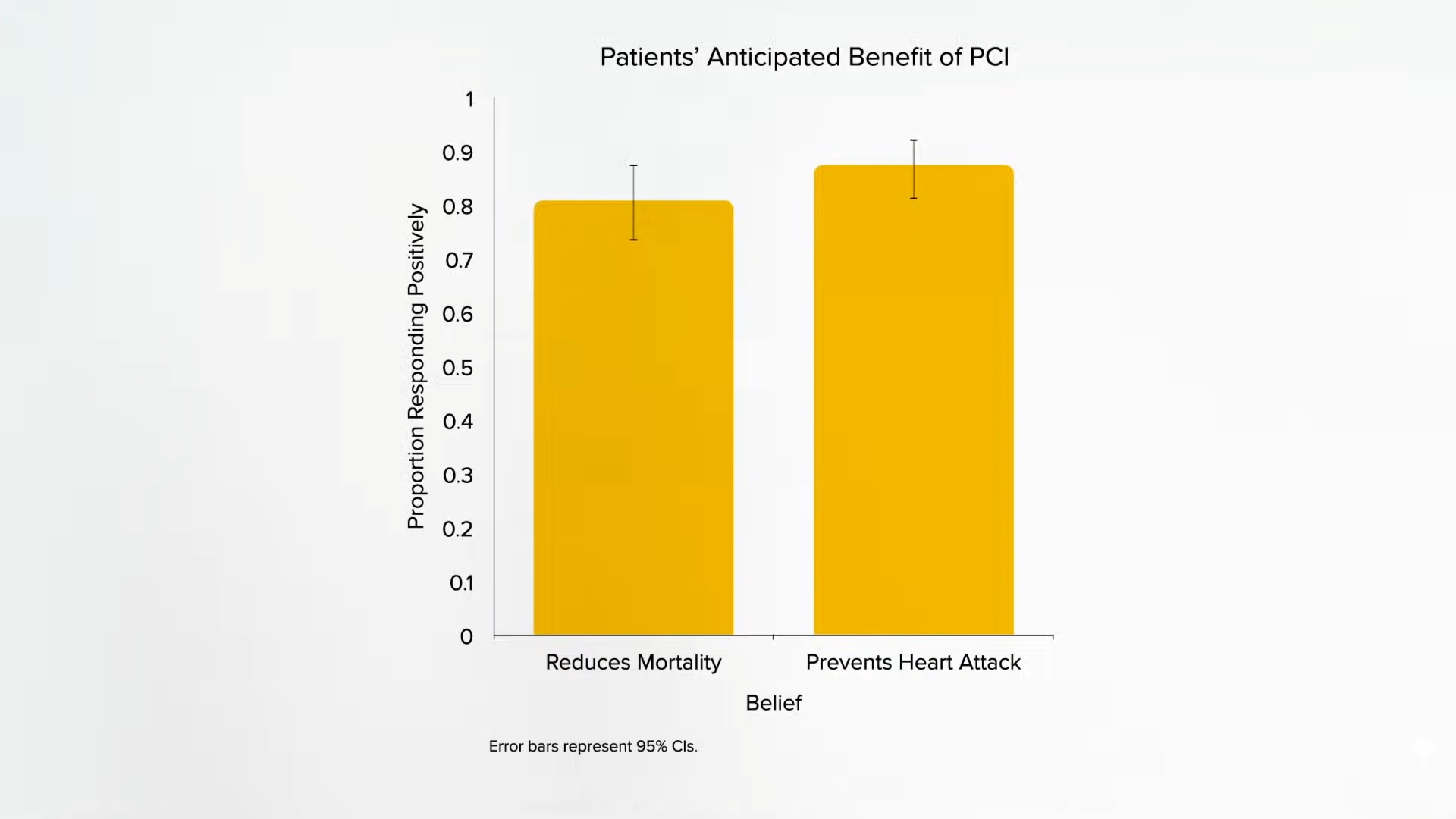

What does the world’s number one stent manufacturer have to say for itself? It acknowledges that the evidence shows that stents don’t make people live longer, but the manufacturer thinks living longer is overrated. If we only cared about living longer, in medicine, “entire disciplines would dwindle or even disappear, such as dermatology, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, and dentistry.” So why go to the dentist? Of course, the difference is that 80 percent of people don’t believe that getting a cavity filled is going to save their life, like they mistakenly do for stents, as shown here and at 3:18 in my video, and there isn’t a one in a hundred chance you won’t make it out of the dentist chair.

The stent companies actively misinform with ads making heart-warming copy. “Open your heart and your life.” “When you open up your heart, you open up your life. LIFE WIDE OPEN.” “Freedom begins here.” Their TV ads mention a few side effects, but it turns out they missed a few. More importantly, they’re giving the false impression that stents are more than just expensive, risky band-aids for temporary symptom relief. But what’s wrong with symptom relief? Even if the benefits are only symptomatic and won’t last long, what’s the problem if people think that outweighs the risk?

What if I told you that even the symptom relief might just be an elaborate placebo effect, and you could get the same relief from a fake surgery, so there really aren’t any benefits at all? We’ll see what the science says—next.