In September of 2013, the simmering rivalry between entrepreneurs Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk reached a fever pitch. NASA’s historic Launch Complex 39A, the launch pad for Apollo 11, was no longer needed, and the agency decided to transfer it to a commercial firm. Musk’s SpaceX and Bezos’ Blue Origin both submitted proposals to renovate the hallowed site. Musk was irate to be facing a challenge from a company which was still early in the development of its own launch vehicle. “If (Blue Origin) does somehow show up in the next 5 years with a vehicle qualified to NASA’s human rating standards that can dock with the Space Station, which is what Pad 39A is meant to do, we will gladly accommodate their needs,” he opined in an e-mail to the media outlet SpaceNews [1]. Frankly, I think we are more likely to discover unicorns dancing in the flame duct.”

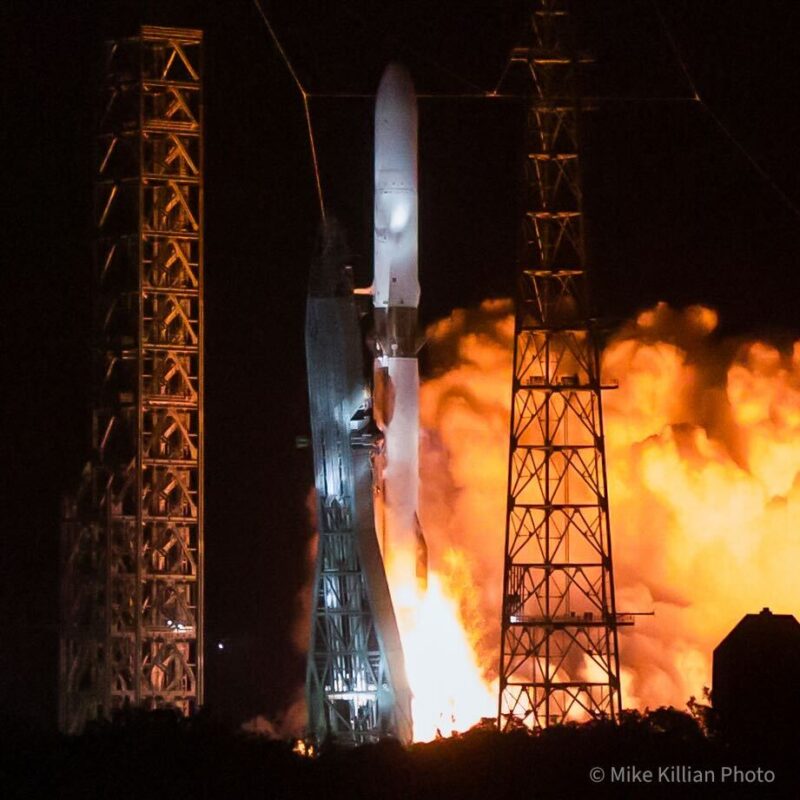

Blue Origin lost its bid to obtain Pad 39A, and as Musk anticipated, the development of its first orbital rocket took more than five years. However, if unicorns existed, they would surely be partying in the company’s flame trench tonight. Early this morning, Blue Origin’s towering New Glenn launch vehicle reached orbit in a nearly flawless debut, marred only by the loss of the first stage during an experimental landing attempt. The successful launch was a major step forward for the company, which aims to become a leading provider of access to space.

As AmericaSpace described in Sunday’s history feature, today’s launch was the culmination of 25 years of innovation and hard work by Blue Origin’s workforce. New Glenn is among the largest rockets in operation, exceeded in height by only SpaceX’s Starship and NASA’s Space Launch System. It stands 320 feet (98 meters) tall, just 40 feet shy of the Saturn V rocket which sent the Apollo astronauts to the Moon 55 years ago.

Blue Origin’s goal is to place 45 metric tons of payload into orbit during each New Glenn launch. However, Ars Technica’s Eric Berger reported that it may be suffering from underperformance issues which are similar to those which SpaceX’s Starship team is attempting to solve. According to these unconfirmed reports, New Glenn’s current payload is approximately half of its design goal [2]. Future iterations of the rocket will feature lighter components in order to reduce parasitic mass and realize its full potential.

Like most operational orbital launch vehicles, New Glenn has two stages. Both utilize cryogenic propellants with extremely low boiling points. The first stage is powered by liquid methane and liquid oxygen to maximize thrust and propellant density; the second stage is loaded with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen to maximize the efficiency of its engines. Each stage has an engine tailored for its unique propellant mixture.

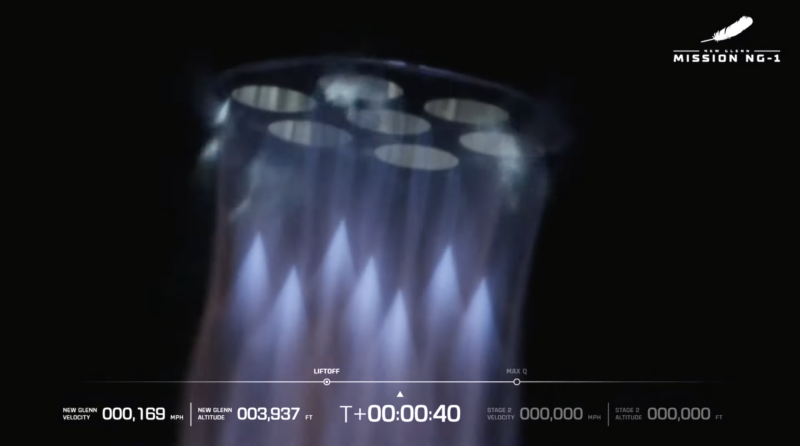

The seven BE-4s on the first stage propel the fully-fueled rocket above the bulk of the Earth’s atmosphere. They were already proven commodities thanks to their role as the main engines on ULA’s Vulcan, which debuted one year ago today. In terms of thrust and propellant mixture, they are roughly equivalent to SpaceX’s Raptor engine. New Glenn and Starship are both second-generation reusable rockets which use methane as fuel. This gives them several advantages over existing launch vehicles.

For instance, the mainstays of the commercial launch industry, including SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and ULA’s Atlas V, use kerosene fuel. In addition to being more efficient than kerosene, liquid methane burns cleanly. When oxygen and methane combust, the only byproducts of the reaction are carbon dioxide and water vapor. This means that the BE-4s do not produce the ubiquitous soot which gradually darkens the hull of a Falcon 9 booster over the course of many flights. Soot clogs the intricate mechanisms inside rocket engines, and engineers must perform additional maintenance between flights to remove it.

As for the second stage, it is accelerated into orbit by twin BE-3U engines. While it was originally supposed to be based upon New Shepard’s main engine, the BE-3U is, in reality, an entirely new motor. To top off the stack, New Glenn’s payloads are encapsulated in a massive fairing which measures 23 feet (7 meters) in diameter. This spacious shroud allows it to launch larger space station modules and satellites than existing rockets, which employ 5-meter fairings. Being able to deploy large payloads is a key capability which will enable Bezos’ envisioned “Road to Space.”

Preparations for New Glenn’s maiden voyage began late in the evening of January 7th. Over the course of three hours, the massive rocket was gradually filled with a full load of propellant. This is no trivial task; hydrogen, in particular, is notorious for leaking. The fact that Blue Origin was able to complete this procedure on its first launch attempt bodes well for routine and regular New Glenn flights in the future. Three seconds before liftoff, the seven BE-4 engines roared to life with 3.85 million pounds of thrust. Florida’s Space Coast trembled under this force; Cocoa Beach, in particular, had a spectacular view of the liftoff.

At T-0, New Glenn was released from its launch pad and took flight for the first time. Much like the Saturn V of old, it lifted off the ground in a ponderous and stately manner, gradually gaining speed as it climbed. As this was a night launch, the ascending rocket turned night into day. Beyond just the power of the first stage, the launch had a unique attribute which set it apart from the rockets which normally grace Cape Canaveral. The exhaust plume was not the warm orange-yellow of the Sun, but a brilliant royal blue. Relativity Space’s much smaller Terran-1 was the only previous rocket to produce a similar hue. Long-exposure photographs of the climbing New Glenn show a sublime blue arc reaching towards the cosmos.

The BE-4s kept burning for 3 minutes and 12 seconds. At this point, the first stage was jettisoned and the two BE-3Us took center stage. Lighting a rocket engine in the vacuum of space, without any massive pieces of ground support equipment, is a deceptively difficult task, and many untested rockets meet their demise at stage separation. This was not the case here. The second stage performed flawlessly for nearly 10 minutes, placing itself and its payload into a stable low Earth orbit.

However, even as this burn was underway, another spectacle was unfolding in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. To reduce New Glenn’s launch costs and increase its flight rate, the first stage is designed to be reusable. Blue Origin made the bold decision to recover the stage on the first flight, and accepted the delay required to prepare for a landing attempt. The booster was intended to alight on the deck of the ship Jacklyn, named in honor of Bezos’ mother. Jacklyn is a stationary robotic barge with a reinforced upper deck. Essentially, it is an upscaled cousin of SpaceX’s famous drone ships.

Seven minutes after it left Earth, the booster performed a short entry burn to prevent it from overheating as it reentered the atmosphere. However, that was the last anyone heard from the stage, which Blue Origin lightheartedly named “So You’re Telling Me There’s a Chance?”. Minutes later, a spokeswoman confirmed that it was lost; as of this writing, the precise cause of the anomaly has not been disclosed.

New Glenn’s first payload was originally supposed to be NASA’s twin ESCAPADE probes, which will study Mars’ magnetic field and its interaction with the solar wind. Unfortunately, the launch was delayed when it became clear that New Glenn would not be available during the 2024 Mars launch window, which opened in October and closed in November. Instead, Blue Origin leveraged its otherwise empty rocket to test key components for its Blue Ring spacecraft. Blue Ring will be a large space tug which can transport up to three metric tons of cargo between different orbits.

Little is known about the Blue Ring pathfinder. It appears to be a minimalist secondary payload dispenser with no power or propulsion systems attached. “The demonstrator includes a communications array, power systems, and a flight computer affixed to a secondary payload adapter ring,” Blue Origin wrote in a press release [3]. “The pathfinder will validate Blue Ring’s communications capabilities from orbit to ground. The mission will also test its in-space telemetry, tracking and command hardware, and ground-based radiometric tracking that will be used on the future Blue Ring production space vehicle.” Blue Origin’s flight control team tested these systems over the course of six hours before New Glenn’s second stage performed a deorbit burn with the pathfinder attached.

After accounting for the loss of the booster, New Glenn’s debut was still a resounding success. Even today, with modern technology and supercomputer-enabled simulations, over 50% of new rockets fail to reach orbit on their first attempt [4]. A disproportionate number of the rockets which do succeed, such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and ULA’s Vulcan, are built by companies which have previously operated orbital launch vehicles. Blue Origin lacked this foundation of knowledge, but still managed to complete a successful mission.

As for the landing attempt, Blue Origin’s CEO, David Limp, clearly stated that it was purely experimental and not part of the mission’s success criteria prior to launch [4]. To land safely, a rocket must autonomously account for gusts of wind, atmospheric friction, the position of the landing pad, and many other variables. New Shepard, Falcon 9, and Starship all required multiple attempts to complete a successful landing, as will New Glenn.

The New Glenn launch was applauded by many of the space industry’s most prominent figures. Bezos and Limp stood together in Blue Origin’s launch control center with smiles plastered across their faces. Current NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and his presumed successor, Jared Isaacman, both attended the launch in person. And, 12 years after Bezos and Musk feuded over Pad 39A, the two titans of industry appear to have made peace. “Congratulations on reaching orbit on the first attempt!”, Musk wrote [5].

Blue Origin’s 10,000 employees are also sure to be celebrating the success of New Glenn’s first launch. The massive rocket is at the crux of the company’s long-term corporate roadmap. While the company is working on many other projects, none of them are plausible unless New Glenn flights are regular and affordable. Furthermore, the completion of New Glenn development will free up engineers and financial capital which can be applied to other initiatives.

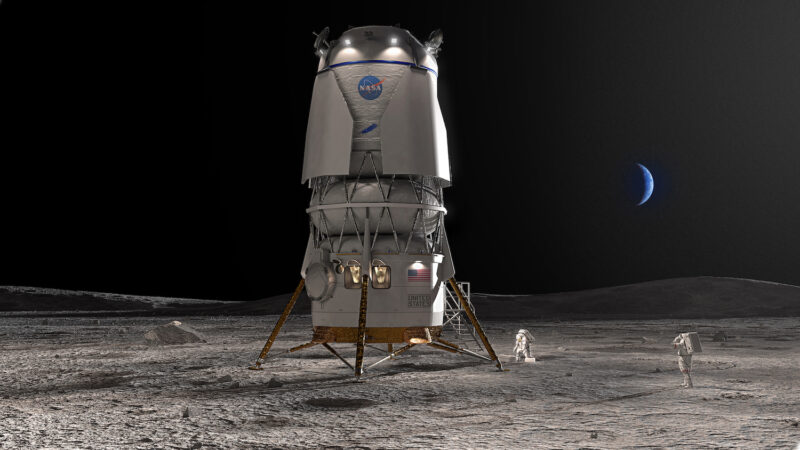

Most importantly, Blue Origin is developing a crewed lunar lander for NASA’s Artemis program. The Blue Moon Mark 2 lander features an innovative design with a crew cabin located at ground level. It is slated to debut during Artemis 5, which will take place no earlier than 2030. New Glenn will launch both the lander and the Cislunar Transporter, a reusable tug which will ferry propellant to lunar orbit. In the long term, Blue Origin aspires to enter the human spaceflight market, and entrusting Blue Origin’s new booster with the lives of astronauts just became a much more reasonable proposition.

New Glenn will conduct several other critical missions for Blue Origin and its customers. It will be used to launch Blue Ring, the modules of the Orbital Reef space station, and a conceptual Blue Origin crew capsule. It will also compete with ULA’s Vulcan and SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy to launch military satellites for the U.S. Space Force. Amazon hopes that New Glenn’s large payload mass, its spacious fairing, and its relatively low unit cost will allow its Kuiper program to compete with SpaceX’s Starlink megaconstellation, which have a massive first-mover advantage in the satellite communications field. Finally, Blue Origin eventually hopes to give New Glenn a reusable second stage to make it even more competitive in the commercial marketplace.

As of September, Blue Origin was planning to launch up to 12 New Glenn missions in 2025 [6]. Needless to say, this is an ambitious goal. The actual launch cadence will depend on the length of the data review following this test flight, as well as whether the company encounters any anomalies during subsequent missions. The 2025 launch manifest will include two high-profile payloads. This spring, Blue Origin intends to launch both ESCAPADE and the first Blue Moon Mark 1 lander, which will land three metric tons of cargo on the lunar surface and test systems for the company’s piloted Artemis lander. New Glenn joins a growing stable of reusable American launch vehicles, which could potentially make a robust space economy possible for the first time in human history.